Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.

That philosophy of reduction is exactly what GenAI can offer trial lawyers, and here’s why that matters. Indeed, I recently talked about how slow and cumbersome the process was, particularly in light of how people learn and digest information in the digital age.

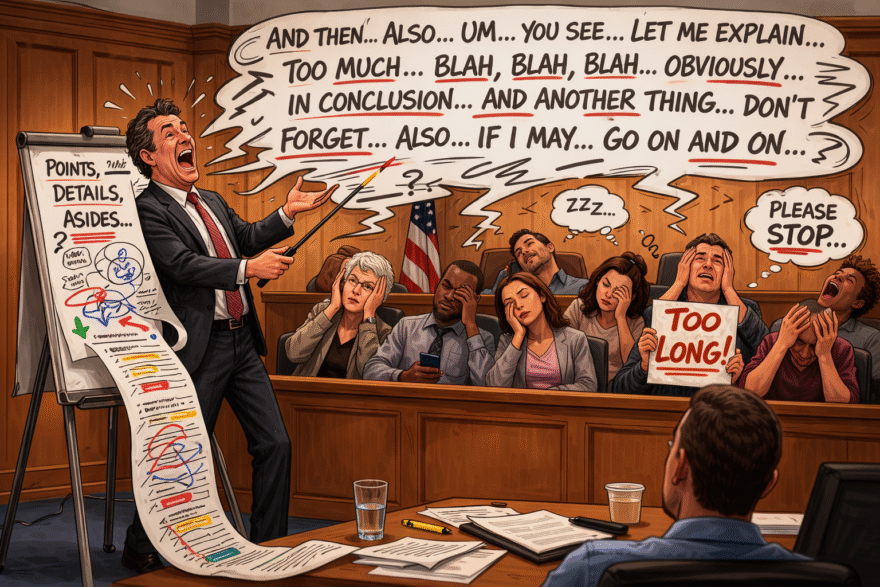

So, when I was recently helping to teach a course on the use of trial technology and one of the faculty members talked about reducing his opening statement in a complex products liability trial to 2 ½ minutes with the help of ChatGPT, my ears perked up.

We were all a bit agog until he played a version of it for us. It was riveting. It hit the points, the themes of the case and what he would prove. And of course, ended with a statement of how he assured the jury he would respect their time. I suspect his opening came on the heels of a long-winded statement by the other side.

He also did something interesting. He took what ChatGPT gave him based on his prompt about his case themes and created an realistic avatar who then performed the opening statement to him. That way he could not only read it but hear what it sounded like. It also gave him clues as to what to emphasize and the voice inflection. And it ensured that the product did not appear to come from GenAI. Of course, he added his own language to parts of the statement to make it real.

I have talked a lot recently about the limitations of GenAI and how it’s often over-hyped and over sold. But that doesn’t mean we should (or ethically can) ignore what it does well and when to use it. And this may be one of them.

As lawyers, we often get hung up with minutiae

As lawyers, we often get hung up with minutiae. We lose respect for the jury and their time. The result is we try to prove the same point over and over. We fear when we make a point, some of the jurors don’t get it. So, we make it again and again. We argue minor points to the judge at bench conferences as the jury looks on bored to tears.

But the beauty of GenAI is that it can help us distill and summarize. To make things clear with less, not more. The irony is that a non-human tool may understand human communication better than many lawyers do.

Here’s a recent example. As many know Derek Chauvin was on trial for the murder of George Floyd by the police. The claim was the police used excessive force in arresting Floyd, causing his death. Chauvin was charged with murder and manslaughter, and the prosecution’s burden was to prove that Chauvin’s use of force was unreasonable and that it caused Floyd’s death.

The trial commenced on March 29, 2021. The prosecution kicked off the trial with an opening statement that went on for over 15 minutes and was well over 2300 words.

Standard thinking was that what the prosecutor needed to communicate was the use of excessive force, the legal standard for police conduct, the duration of the restraint, medical causation, and anticipated defenses. Standard thinking would also suggest the need to humanize George Floyd, define the meaning of causation, and preview video and medical evidence. Given all the perceived needs, most would concede that 15 minutes was pretty concise.

But with attention spans as short as they are these days, even 15 minutes might be a long time.

That was my initial reaction as well. But with attention spans as short as they are these days, even 15 minutes might be a long time.

I asked ChatGPT to compress those essential elements into a concise opening that could be delivered in roughly two and a half minutes. Here is the result:

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury:

On May 25, 2020, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the defendant, Derek Chauvin, used excessive and unreasonable force against George Floyd. He kept his knee pressed into Mr. Floyd’s neck and back for nine minutes and twenty-nine seconds.

During those nine minutes and twenty-nine seconds, Mr. Floyd was handcuffed. He was lying face down on the pavement. He was not resisting. He told the officers he could not breathe. Bystanders pleaded with the defendant to stop. Fellow officers raised concerns. Still, the defendant continued.

You will see this with your own eyes.

This case is about what happened in those nine minutes and twenty-nine seconds. The evidence will show that the defendant’s restraint went far beyond what police training and the law allow. Officers may use force, but only reasonable force. And force that is no longer necessary must stop.

Here, it did not stop.

You will see that the defendant maintained pressure even after Mr. Floyd became motionless. Even after he lost consciousness. Even after there was no pulse. The defendant did not remove his knee until paramedics arrived.

The medical evidence will show why that matters. George Floyd died from low oxygen caused by the defendant’s restraint. The position, the pressure, and the duration deprived him of the ability to breathe.

You will hear from police trainers who will explain that this restraint violated department policy and basic safety principles. You will hear from medical experts who will explain how the restraint caused death. And you will see the video — the bystander video and the body-camera video — that captured these events in real time.

You can believe your eyes.

The law applies equally to everyone. The badge does not permit unreasonable force. And when an officer uses force that is excessive, unnecessary, and prolonged — force that causes death — the law calls that a crime.

At the end of this trial, after you have seen the evidence and heard the testimony, the State will ask you to return verdicts of guilty on all counts.

This statement is 360 words and when I practiced it, it took about 2 ½ to 3 minutes. Particularly effective was the use of “you can believe your eyes” versus the video tapes will show. And if I were giving this statement, I would of course tweak various portions but still keep it with the time frame. But if you were sitting in the jury box for what would turn out to be three weeks which version would you rather hear? Which is more effective?

We need to focus less on quantity and more on quality

As trial lawyers, all too often we don’t trust jurors. We think we have to beat them over the heads with evidence and our case themes. In fact, though, we need to focus less on quantity and more on quality. How we can get their attention, respect their time and teach them in ways they learn in everyday life. One thing GenAI does well is to do just that.

So why aren’t you using it?